IHC Strategy

People with intellectual disability clearly value tangible outcomes and self-determination. They demand the right to pursue their interests, learn, engage in meaningful activities, including work, and achieve independence with appropriate support and control over their home.

Families strongly echo this, expressing concern over limited personal growth opportunities and the significant post-school void, urging action to help communities better recognise their members' value and contributions.

Digital barrier:

Less than 50% of intellectually disabled people 55+ have access to the internet.

Educational exclusion:

57% of adults with intellectual disability have no qualifications. This compares to 12% of the general population.

Employment exclusion:

Only 21% of people with intellectual disability are in paid employment. 78% of the general population are in paid employment.

There is a powerful demand for strong, visible, systemic advocacy led by IHC, driven by the need to ‘leave no one behind’ and ensure those who cannot speak for themselves are represented.

Families believe advocacy is really important and want IHC to lead by sharing knowledge and having the courage to question issues that adversely affect people’s lives.

Families are ready to be an ally in IHC’s advocacy work, supporting and working alongside IHC at local and national levels.

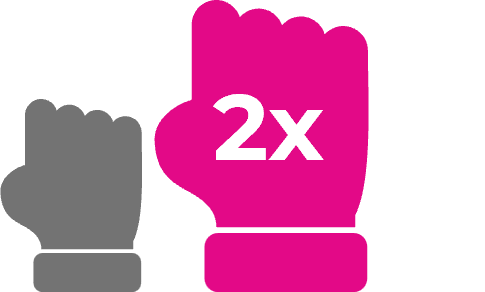

Hardship:

People with an intellectual disability are twice as likely to live in hardship or severe hardship

Families are clear: the system is complex and hard to navigate. Many respondents don't know where to go for help, information and support. They face a lack of good information and lots of barriers.

Families want IHC to consider its role to make information more accessible and useful, while also ensuring IHC is transparent and open about its own plans, and the overall approach is kept simple.

Safety and security are paramount. Families raised significant concerns about the well-being of people with intellectual disabilities, particularly for those living on their own or when parents become less involved. This fear is compounded by anxiety over what happens when families are no longer there to support and advocate for their family member. A clear message was also received about the foundational need for good health and housing.

Victims of crime:

Adults with intellectual disability are over 3 times more likely to be a victim of crime than people in the general population.

Exposure to violence:

Children with intellectual disability are almost twice as likely to be exposed to family violence as children in the general population

Preventable harm:

People with intellectual disability are 3.6 times more likely to be admitted to the emergency department for conditions that could’ve been avoided.

Both people with intellectual disabilities and families emphasised the importance of opportunities to form friendships and relationships. Families demand that connecting families and local communities needs to be a focus, urging IHC to be a place where brave conversations happen, leadership is nurtured, and people feel empowered. Finally, the value of relationships with capable, committed staff was highlighted as essential to quality support.

Living alone:

Adults with intellectual disability are twice as likely to not live in a family nucleus.

Post-school void:

Young people with intellectual disability are over 3 times more likely not to be in education employment or training (41%).

People with intellectual disability said choice over where they live and who they live with, and what happens in their home, is very important to them.

Social housing:

People with intellectual disability are much more likely to use social housing, indicating that private housing is unaffordable for them and their whānau.

Poor housing:

People with intellectual disability are 38% more likely to live in overcrowded conditions.