Categories

“We just keep going” – the hidden cost of exclusion

New IHC research has confirmed what many families already know: for people with an intellectual disability, hardship is more common, more severe and more enduring.

Drawing on data from Stats NZ Integrated Data Infrastructure, the report shows that people with an intellectual disability are twice as likely to experience hardship up to age 39 – and almost three times as likely in middle age. While hardship tends to ease for other New Zealanders over time, the opposite is true for people with intellectual disability.

The findings are stark. Half of people with intellectual disability could not pay an unavoidable bill within a month without borrowing – nearly three times the rate of the general population. People with an intellectual disability were also four times more likely to say they couldn’t afford a meal with meat, or a vegetarian protein equivalent, every second day, and three times more likely to cut back on fresh fruit and vegetables because of cost.

The ripple effects of poverty

People with an intellectual disability are over three times more likely to lack access to a car, over twice as likely to go cold because of heating costs, and almost half are unable to afford a holiday.

For families this is exhausting.

“I ended up working full-time for three years, which just about killed me,” says Riley, mother of Simon. “50 hours a week plus 15 to 20 hours advocating for Simon, payroll for carers and dealing with OTs [occupational therapists] … It was like running a small business just for his care.”

In the research report, parents told us that navigating the system was a full-time job in itself, based on proving over and over again what their child cannot do.

Parents shared the difficulties in securing individualised funding for their child and the pain they experience when filling in endless forms to detail how their child can’t do things most children their age can. “It runs on a deficit model – by what a kid can’t do rather than who they are… And so I have to outline exactly, basically, what my god-daughter can do and what Meleia can’t do,” says Lani, Meleia’s mother.

Families also spoke about being forced to make impossible choices – between income and caregiving, between medical appointments and job security, between what their child needs and what they can actually get.

Hardship starts young

The research found that children with intellectual disability are missing out on the basics of childhood because of cost. Compared to other children, they are:

- over 6.5 times more likely to miss school events

- twice as likely to miss out on fresh food every day

- nearly 30% are unable to afford to have friends over to eat occasionally

And the housing picture is no better. People with intellectual disability are up to four times more likely to rent, and over seven times more likely to live in social housing. Across every age group, they are far more likely to live in New Zealand’s most deprived neighbourhoods.

Why this matters

Families told us that hardship is about having to fight harder to receive less. It’s about living on the back foot, where a delay in one part of life (like getting a diagnosis or securing funding) causes a ripple effect across everything else – health, education, work, even hope.

The report shows what IHC has known for many years, that families are resourceful, determined and doing everything they can. But the support systems around them are not. Support is often tied to diagnosis rather than need. Processes are complex, time-consuming and emotionally exhausting. The result is that families are on the edge and people with intellectual disability are being denied a good life.

What we’re calling for

The findings show urgent changes are needed to the systems designed to serve intellectually disabled people, including income support for people with an intellectual disability and their families. That means timely diagnoses, accessible funding processes, adequate disability support, and a commitment across government to stop locking people with intellectual disability out of basic needs.

Because, as this research makes clear, poverty is not inevitable – let’s make it unacceptable.

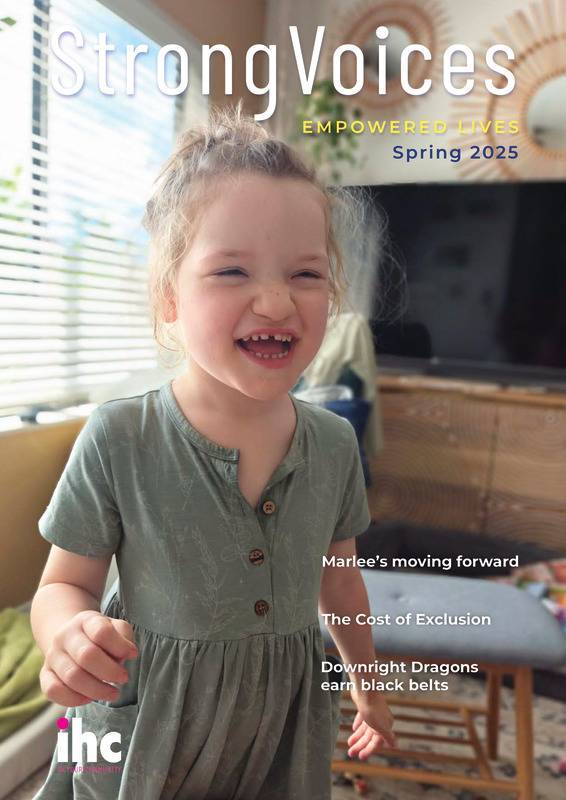

Image caption: Right: (From left) National Self-Advocacy Advisor David Corner, Tania Thomas, Senior Advocate Shara Turner and one of the report’s authors Keith McLeod.

This story was published in Strong Voices. The magazine is posted free to all IHC members.

Download PDF of Strong Voices issue